When exactly people began occupying the Fort McMurray area is a question that has been puzzling archaeologists for decades.

There is a wealth of evidence that humans have been in the area a long time – nearly 3.8 million artifacts have been recovered from more than 1,000 sites over the past 50 years. But determining how old they are isn’t as simple as it might seem.

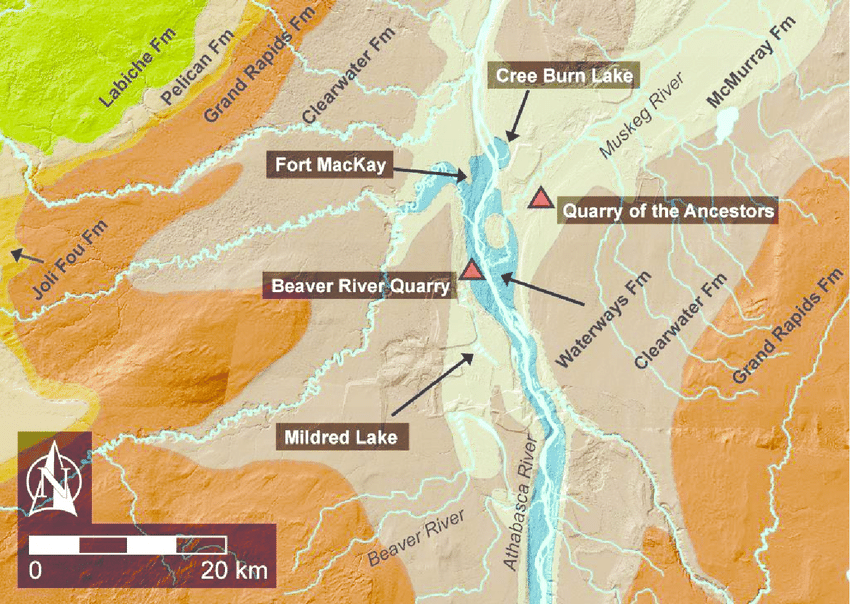

Most artifacts are stone tools, including arrowheads, made from the area’s rich deposits of Beaver River sandstone.

“By the early 2000s, scientists had worked out that there was a big flood about 13,000 years ago that exposed the sandstone that people were using to make tools found in archaeological sites,” explains Dr. Robin Woywitka, assistant professor in Earth and Planetary Sciences at MacEwan.

But because the most common and accurate dating tool used in archaeology – radiocarbon dating – requires organic material (and acidic forest soils tend to destroy artifacts made of wood, bone and plant fibres), archeologists were left with stone artifacts they weren’t able to directly date.

“We could never say whether the sites we found were 13,000 years old or 1,000 years old, or a mixture of everything in between,” says Dr. Woywitka.

So Dr. Woywitka teamed up with colleagues Dr. Duane Froese from the University of Alberta, Dr. Michel Lamothe from the Université du Québec à Montréal and Dr. Stephen Wolfe from the Geological Survey of Canada to use a blend of archaeology and geology to put a date on exactly when people first inhabited the area.

The first step was finding a site with clear layering to ensure they weren’t dealing with a mix of artifacts from different periods. Once they identified a suitable location (it happened to be located right within Quarry of the Ancestors, the source of raw materials for the tools), they used infrared stimulated luminescence (IRSL) – but not to date the artifacts directly.

The first step was finding a site with clear layering to ensure they weren’t dealing with a mix of artifacts from different periods. Once they identified a suitable location (it happened to be located right within Quarry of the Ancestors, the source of raw materials for the tools), they used infrared stimulated luminescence (IRSL) – but not to date the artifacts directly.

“We couldn’t date the artifacts themselves, but we could use IRSL to date the dirt that encased them,” explains Dr. Woywitka.

The process uses the concept of radioactive decay, he explains. Grains of sand made up of feldspar or quartz have tiny imperfections – basically little holes that fill up with electrons from naturally occurring radioactive elements in the environment. The longer those grains of sand stay buried and unexposed to light, the more radioactivity gets trapped in the holes.

The researchers collected samples from the site, kept them in the dark, took them into the lab, then stimulated them with light. When the light hit the little holes trapping the radioactive elements, they emptied, releasing light.

“By measuring the strength of the light they release, we can figure out how much energy was trapped,” says Dr. Woywitka. “And because we know the rate of radioactive decay in that environment – in other words, the rate that energy accumulates – we can calculate the time the grain of sand was buried.”

With a 10 per cent margin of error, the technique is a little less precise than radiocarbon dating. In this case, the sediments in which the archaeological artifacts were buried turned out to be 12,000 years old (give or take 1,200 years).

They further confirmed the date, says Dr. Woywitka, by looking at the sedimentary structures at the site, including sediment-filled ice wedges indicating permafrost.

The stratigraphic sequence at Quarry of the Ancestors that Dr. Woywitka and his colleagues excavated and sampled. The dip in the middle is an ice wedge cast. Photo courtesy of Dr. Woywitka.

The stratigraphic sequence at Quarry of the Ancestors that Dr. Woywitka and his colleagues excavated and sampled. The dip in the middle is an ice wedge cast. Photo courtesy of Dr. Woywitka.

“We knew that the earliest time permafrost could have been sustained for long enough to create that structure would have been around the Younger Dryas period – around 12,000 years ago.”

Read the full paper published in Quaternary Research.

So with this mystery solved, what’s next?

“This finding has implications that extend beyond archaeology,” says Dr. Woywitka. “We hope to work with Indigenous communities to understand and learn more about their deep connection to the oil sands area and its role as an important meeting place during protohistoric and historic times.”